.356 TSW

.356 TSW

The .356 TSW Cartridge: A Potent but Overlooked Round

The .356 TSW (Team Smith & Wesson), also known as 9x21.5mm TSW, is a centerfire pistol cartridge developed by Smith & Wesson in the early 1990s. Designed with competitive shooting in mind, it was intended to dominate International Practical Shooting Confederation (IPSC) and United States Practical Shooting Association (USPSA) Limited-division matches. Despite its impressive performance, rule changes and marketing missteps relegated it to obscurity. Recent interest, however, has sparked a niche revival, positioning the .356 TSW as a compelling option for self-defense and enthusiasts of unique firearms. This article explores the cartridge’s history, technical specifications, performance, and modern relevance.

Origins and Purpose

Introduced in 1993, the .356 TSW was crafted to meet the needs of IPSC and USPSA competitors seeking a high-performance round that could achieve a "major power factor" in Limited division while maintaining the magazine capacity of a 9mm platform. The power factor, calculated as bullet weight (in grains) multiplied by velocity (in feet per second) divided by 1,000, needed to exceed 175 to qualify as "major." The .356 TSW delivered, with a 147-grain bullet at 1,240 feet per second (fps) producing a power factor of 182 from a 5-inch barrel.

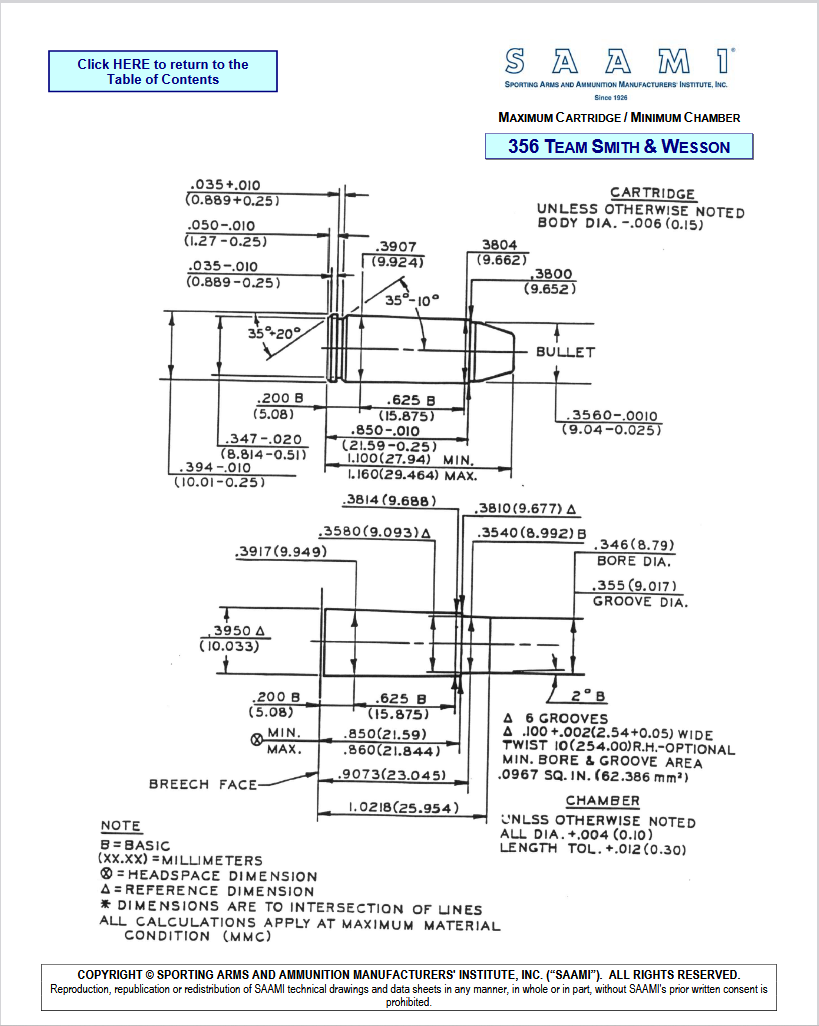

Smith & Wesson partnered with Federal Cartridge Company to develop and produce the round, which was submitted for Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) approval. The cartridge was chambered in specialized firearms, including the Smith & Wesson Model 3566 Performance Center pistols (available in 5-inch and 3.5-inch barrel variants) and a limited run of J-frame Model 940 revolvers. Some models, like the Super 9 (a modified 5906), even included interchangeable barrels for 9x19mm Parabellum, 9x21mm, and .356 TSW.

The .356 TSW’s straight-walled case, slightly longer than the 9mm Parabellum at 21.59mm, allowed it to fit standard 9mm magazines while supporting higher pressures (up to 50,000 psi, compared to 35,000 psi for standard 9mm). This design offered up to 40% more muzzle energy than 9mm Parabellum, rivaling the bottlenecked .357 SIG in power but with greater magazine capacity. For example, a Glock 19 chambered in .356 TSW holds 15 rounds, compared to 13 for the same model in .357 SIG.

Rise and Fall

The .356 TSW’s competitive edge was short-lived. In the mid-1990s, IPSC and USPSA revised their rules, requiring cartridges to be at least .40 caliber to qualify for major power factor in Limited division. This change rendered the .355-inch diameter .356 TSW ineligible, stripping away its primary purpose. Smith & Wesson attempted to rebrand it as the .356 Tactical Smith & Wesson for self-defense and law enforcement, but the cartridge struggled to gain traction. Federal’s primary duty load—a 147-grain bullet at a modest 987 fps—offered little advantage over standard 9mm, further hampering its appeal.

Production dwindled, and by the late 1990s, the .356 TSW had largely vanished from the mainstream. Federal and Corbon, the primary ammunition manufacturers, ceased production, leaving only a small group of enthusiasts to keep the cartridge alive. Its obscurity was compounded by the limited number of firearms chambered for it, with estimates of 300–500 Model 3566 pistols, 100 Briley Comp models, 180 J-frame revolvers, and 100–200 Super 9 pistols produced.

Performance and Ballistics

The .356 TSW’s design prioritized high velocity and energy in a compact package. Its straight-walled case avoids the case neck separation issues that plagued early .357 SIG ammunition, and its compatibility with standard 9mm bullets (0.355 inches) simplifies reloading. The cartridge’s high pressure allows it to achieve velocities comparable to .357 Magnum and .357 SIG loads, making it a formidable option for both competition and self-defense.

Historical and modern loadings demonstrate its capabilities:

-

Federal (1990s): 147-grain FMJ at 1,240 fps (182 power factor) and 147-grain Hydra-Shok JHP for self-defense. A 135-grain JHP was also offered.

-

Corbon (1990s): 124-grain JHP at 1,450 fps, matching .357 Magnum performance from a 4-inch barrel.

-

Corbon (Modern): 115-grain JHP at 1,600 fps, delivering 654 foot-pounds of muzzle energy.

-

Underwood (Modern): 115-grain JHP at 1,600 fps (654 ft-lbs) and 124-grain JHP at 1,450 fps (579 ft-lbs). Both are supersonic and suppressor-safe, with sectional densities values of 0.130 and 0.140, respectively, indicating good penetration potential.

These figures highlight the .356 TSW’s ability to deliver .357 SIG-level performance in a smaller, higher-capacity package. Its recoil is stout, comparable to .357 SIG, but manageable in modern firearms like rechambered Glock 17s or 19s.

Revival and Modern Relevance

In the late 2010s, renewed interest in the .356 TSW emerged, driven by enthusiasts like Scott Sullivan, a retired military member and firearms aficionado. Sullivan collaborated with Corbon and Underwood to resume ammunition production, with Starline Brass and Hornady supplying cases. He also worked with Briley to produce conversion barrels for Glock 17 (Gen 1–4) and Glock 19 (Gen 1–5), complete with upgraded recoil springs (20–22 lbs) and guide rods to handle the cartridge’s higher pressure. These kits, available for around $300, have made the .356 TSW accessible to owners of popular Glock models.

The cartridge’s modern appeal lies in its niche applications. For self-defense, its high velocity and energy make it a potent alternative to 9mm +P or .357 SIG, with the added benefit of greater magazine capacity. Enthusiasts have even rechambered compact platforms like the SIG P365 for .356 TSW, reporting reliable performance with Underwood ammunition and compatibility with standard 9mm rounds in a pinch.

For collectors and hobbyists, the .356 TSW represents a fascinating piece of firearms history. Its rarity—coupled with the limited production of compatible firearms—adds to its allure. Ammunition remains available through Underwood and Corbon, though brass can be expensive and difficult to source. Reloading is viable using 9mm dies adjusted for the longer case, with load data similar to 9x21mm.

Challenges and Future Outlook

Despite its strengths, the .356 TSW faces significant hurdles. Ammunition availability is limited, and costs are higher than for mainstream calibers like 9mm or .40 S&W. The cartridge’s niche status and lack of widespread firearm support deter mass adoption. Additionally, its advantages over .357 SIG (primarily magazine capacity) may not outweigh the established popularity of other rounds for most shooters.

The .356 TSW’s future likely depends on dedicated enthusiasts and small-scale manufacturers. While a full comeback is improbable, its revival demonstrates the enduring appeal of high-performance rounds in compact packages. For those willing to invest in conversion kits or rare Smith & Wesson models, the .356 TSW offers a unique blend of power, capacity, and historical intrigue.

Conclusion

The .356 TSW is a cartridge ahead of its time, undone by rule changes and poor marketing but rediscovered for its raw potential. Its ability to deliver .357 SIG-like ballistics with 9mm magazine capacity makes it a compelling choice for self-defense and specialty applications. Though it remains a niche round, the efforts of enthusiasts like Scott Sullivan and manufacturers like Underwood and Corbon ensure it won’t fade entirely into obscurity. For shooters seeking a powerful, unconventional cartridge, the .356 TSW deserves a second look.

==============================================================================================

.356 TSW and Its Relation to 9mm Major

The .356 TSW (Team Smith & Wesson) and 9mm Major are two high-performance pistol cartridges rooted in the world of competitive shooting, particularly within the International Practical Shooting Confederation (IPSC) and United States Practical Shooting Association (USPSA). Both were designed to achieve the "Major" power factor in competition, but their paths diverged due to design, marketing, and rule changes. This article explores the origins, characteristics, and relationship between the .356 TSW and 9mm Major, shedding light on their shared goals and distinct fates.

Origins and Purpose

.356 TSW

Introduced by Smith & Wesson in the early 1990s, the .356 TSW (9x21.5mm) was engineered for IPSC and USPSA Limited Division competitions. It was designed to deliver Major power factor performance—typically a power factor of 165 or higher in USPSA, calculated as bullet weight (grains) multiplied by velocity (feet per second) divided by 1,000—while maintaining the magazine capacity of a 9mm platform. The .356 TSW features a slightly longer and significantly stronger case than the 9x19mm Parabellum, allowing for higher pressures (up to 50,000 psi) and greater muzzle energy, reportedly up to 40% more than standard 9mm loads.

Smith & Wesson aimed to create a cartridge that could launch a 124-grain bullet at approximately 1,450 feet per second (fps) or a 147-grain bullet at 1,240 fps, achieving a power factor around 182. Federal and Cor-Bon produced ammunition, with notable loads like Cor-Bon’s 124-grain JHP at 1,450 fps and later Underwood’s 115-grain JHP at 1,600 fps. The cartridge was chambered in Performance Center pistols like the Model 3566 and a rare J-frame Model 940 revolver, marketed as the “Pocket Rocket.”

However, IPSC and USPSA rule changes in the mid-1990s, requiring a minimum caliber of 0.40 inches for Major power factor in Limited Division, rendered the .356 TSW ineligible. This, combined with poor marketing and limited ammunition availability, led to its commercial failure, relegating it to obscurity until a niche revival in the 2010s.

9mm Major

9mm Major, unlike the .356 TSW, is not a distinct cartridge but a specialized loading of the 9x19mm Parabellum, pushed to extreme velocities to meet Major power factor requirements. Before the .356 TSW, competitive shooters in IPSC’s Open Division experimented with “hot” 9mm loads, often using 115- to 124-grain bullets at velocities exceeding 1,400 fps. These loads were controversial due to safety concerns, as the 9mm Parabellum case was not designed for such high pressures (SAAMI maximum is 35,000 psi, with +P at 38,500 psi).

The practice of loading 9mm to Major power levels was initially banned in USPSA for safety reasons, prompting the creation of the .356 TSW as a safer alternative with a stronger case. However, in IPSC’s Open Division, where compensators and optics mitigate recoil and muzzle rise, 9mm Major gained traction. By the 2000s, advancements in reloading techniques and stronger modern 9mm pistols (like the CZ Czechmate and STI 2011 variants) made 9mm Major viable and popular, especially as USPSA lowered the Major power factor threshold to 165 and allowed 9mm Major in Open Division.

Technical Comparison

Cartridge Design

-

.356 TSW: A 9x21.5mm straight-walled cartridge with a reinforced case, designed to handle pressures up to 50,000 psi. It uses standard 9mm bullets (0.355-inch diameter) and has the same overall length as 9mm Parabellum, allowing it to fit in 9mm magazines. This design offers higher magazine capacity compared to bottlenecked cartridges like the .357 SIG, which requires .40 S&W-sized magazines.

-

9mm Major: A 9x19mm Parabellum case loaded to exceed standard pressure limits, often approaching or surpassing 40,000 psi. It uses the same 9mm bullets but requires careful reloading to avoid catastrophic failures, as the case is not as robust as the .356 TSW’s. Modern 9mm Major loads typically push 115-grain bullets to 1,450–1,600 fps or 124-grain bullets to 1,350–1,400 fps to achieve a power factor of 165 or higher.

Performance

-

.356 TSW: Factory loads demonstrate impressive performance. For example, Cor-Bon’s 115-grain JHP achieves 1,612 fps from a 4.5-inch barrel, delivering over 650 foot-pounds of energy. Underwood’s 124-grain JHP reaches 1,391 fps, comparable to .357 SIG. Recoil is described as snappy but manageable, similar to a hot .40 S&W or .357 SIG.

-

9mm Major: Performance depends on the load, but typical Open Division loads include 124-grain bullets at 1,400 fps or 115-grain bullets at 1,600 fps, yielding power factors of 173–184. These loads produce significant recoil and muzzle blast, mitigated by compensators. The energy is slightly lower than .356 TSW due to the case’s pressure limitations, but still formidable.

Safety and Reliability

-

.356 TSW: Its stronger case reduces the risk of case ruptures, making it inherently safer for high-pressure loads. The straight-walled design also improves feeding reliability compared to bottlenecked cartridges like .357 SIG, which faced early issues with case neck separations.

-

9mm Major: Requires robust firearms with fully supported chambers to handle the extreme pressures. Reloading must be precise, as overpressure can lead to case failures or firearm damage. Modern pistols designed for 9mm Major, like 2011-style platforms, mitigate these risks, but the cartridge remains a handloader’s domain.

Relationship and Shared Context

The .356 TSW and 9mm Major are closely related as solutions to the same problem: achieving Major power factor in a 9mm platform for competitive shooting. The .356 TSW was essentially a factory-backed, purpose-built version of what 9mm Major tried to accomplish through custom reloading. Both aimed to combine high velocity and energy with the high magazine capacity of 9mm magazines, offering an edge over larger calibers like .40 S&W or .45 ACP, which held fewer rounds.

The .356 TSW was developed partly because 9mm Major was deemed unsafe by USPSA in the early 1990s, as standard 9mm cases struggled with the pressures needed for Major power factor. Smith & Wesson’s solution was a cartridge that could safely handle those pressures while retaining 9mm magazine compatibility. However, when IPSC and USPSA changed rules to exclude 9mm-caliber cartridges from Major scoring in Limited Division, the .356 TSW lost its competitive niche. Meanwhile, 9mm Major found a home in Open Division, where safety concerns were offset by specialized firearms and compensators.

Ironically, the .356 TSW’s failure paved the way for 9mm Major’s resurgence. As firearm designs improved and USPSA relaxed restrictions, 9mm Major became the preferred choice for Open Division shooters, leveraging widely available 9mm brass and components. The .356 TSW, despite its technical advantages, struggled with limited ammunition availability and lack of mainstream adoption.

Modern Relevance and Revival

.356 TSW

In the 2010s, enthusiasts like Scott Sullivan revived interest in the .356 TSW, convincing Underwood and Cor-Bon to resume production. Conversion kits for Glock 17 and 19 pistols, featuring Briley barrels, became available, allowing shooters to rechamber 9mm firearms for .356 TSW. These kits, priced around $300, cater to niche shooters seeking .357 SIG-like performance with 9mm magazine capacity. The cartridge also found a small following in ICORE revolver competitions, where its longer case improved extraction in moon-clip revolvers like the S&W 929.

Despite this revival, the .356 TSW remains a boutique cartridge. Ammunition is expensive and scarce compared to 9mm, and its primary appeal lies with collectors, reloaders, and those intrigued by its history. Its performance edge over 9mm Major is marginal in practical terms, and the lack of competitive sanctioning limits its use.

9mm Major

9mm Major thrives in USPSA Open Division, where it is the dominant cartridge due to its balance of capacity, recoil, and compensator efficiency. Modern race guns, like the STI 2011 and CZ Czechmate, are optimized for 9mm Major, and reloaders have access to abundant 9mm brass and components. The cartridge’s popularity is bolstered by its versatility—shooters can use the same pistol for standard 9mm loads in other divisions—making it far more practical than the .356 TSW.

Conclusion

The .356 TSW and 9mm Major share a common lineage as high-performance 9mm-based cartridges designed for competitive shooting. The .356 TSW was a safer, factory-supported attempt to formalize what 9mm Major achieved through custom reloading, but rule changes and marketing missteps doomed it to obscurity. 9mm Major, despite early safety concerns, found a lasting niche in Open Division, leveraging advancements in firearm design and widespread component availability.

Today, the .356 TSW is a fascinating footnote, appealing to enthusiasts who value its technical merits and historical significance. 9mm Major, conversely, is a cornerstone of practical shooting, proving that sometimes the less formal solution wins out. Both cartridges highlight the ingenuity of shooters and manufacturers in pushing the limits of the 9mm platform, even if only one remains in the spotlight.

9x19 356TSW 357Sig

E-mail:Admin@9mmMajor.com